British / English Silver Hallmarks

British silver hallmarks were first introduced in 1327. After this date, it was an offence to sell any precious metal without the appropriate hallmarks. Buyers of antique silver products made in the UK should therefore notice several different hallmarks stamped into the surface of the pieces they are buying. Hallmarks are required on all pieces of silver and precious metal including jewellery. These hallmarks tell buyers something about the purity of the silver, when the piece was manufactured and who manufactured it. It is now illegal in most countries to sell commercial silver without the appropriate hallmarks.

Four silver hallmarks are still used today. To the untrained eye, the hallmarks look like nothing more than artistic enhancements. But they are so much more than that. The trained silver trader can instantly tell the value of a piece simply by observing its hallmarks. In Great Britain, silver hallmarks were introduced in the 1320s. From 1327 onward, it became an offence to sell any precious metal in Great Britain and its territories without appropriate hallmarks. This long history of British hallmarks makes our hallmarking system one of the most highly structured and respected in the world.

A total of seven different hallmarks have been used in the British system over the last 600 years or so. Four remain in force while three have been discontinued.

THE STERLING MARK

The sterling mark is intended to indicate the purity of the silver used in the piece. Pieces assayed in England will bear a sterling mark in the image of a lion passant (profile from the side). Other marks indicating the sterling standard have included the Britannia and 958 marks. Scotland's sterling mark is a thistle while Ireland's is a crowned harp. Pieces carrying any of these sterling marks have a confirmed silver content of at least .925 (925/1000)

THE ASSAY MARK

To assay silver is to analyse it and confirm its purity. Pieces that have been analysed and tested receive an assay mark identifying where the test was carried out. Since the beginning of British Silver hallmarks, there have been as many as 11 assay offices with the authority to test and mark silver. Currently, there are only four remaining offices in the UK.

LONDON

Leopards Head, 1544-Present Day

BIRMINGHAM

An Anchor, 1773-Present Day

SHEFFIELD

The York Rose, 1975-Present Day

A Crown, 1755-1975

EDINBURGH

Castle, 1457-Present Day

Birmingham

As mentioned above, the Birmingham hallmark is an anchor. From 1975 onwards, the Birmingham hallmark was amended to be used on platinum and gold; an anchor placed on its side. Since 1999, it has become customary for the anchor to be on its side for gold, platinum, and also silver. If you have a sideways anchor on your silver then you know it is a relatively modern Birmingham creation.

The Birmingham assay office is the largest in the world, and is still a busy office today. Its services extend from hallmarking to valuations and diamond and gemstone certifications.

London

In many ways, London was the ultimate birthplace of the tradition of hallmarking. The term ‘hallmark’ originates in London in the 1400s, when craftsmen in the city brought their goods to Goldsmith’s Hall for assaying and marking. The original hallmark given was the King’s mark – a leopard’s head. The Goldsmith’s Company – the London assay office’s title – would take the mark for their own in 1544, and to this day it is acknowledged as the mark of the London assay office.

The expertise that has been perfected in London over centuries is still used today, creating peerless excellence and comprehensive hallmarking.

Sheffield

Sheffield’s silver-related claim to fame comes from Thomas Bolsover’s creation of fuse plating. This unique technique of silversmithing became known as Sheffield Plate, and is something that is widely collected today. The hallmark for silver being assayed in Sheffield has changed. From its opening in 1773, the hallmark was a crown. In 1974, however, Sheffield’s mark became the Yorkshire rose. This offers silver owners an opportunity to immediately identify basic eras for their Sheffield silver.

Edinburgh

Something unique about the Edinburgh assay office is that – from 1759 to 1874 – Scottish silver and gold bore a thistle hallmark. In 1975, however, this was changed to a rampant lion. No other British assay office has had so many hallmarks, but thanks to the thorough documentation of assay offices, it is still easy enough to identify whether or not your piece has Scottish origins.

Although there has been total refurbishment of the Edinburgh assay office, the quality of the services provided remains excellent and dedicated.

Current Irish Assay Office

- Dublin Assay Office (Crowned Harp) 1637 – present day

In case you're interested, the other UK assay offices (and their marks) that are now closed are as follows:

- Glasgow (a tree) closed in 1964

- Chester (a shield with sheaves of corn) closed in 1962

- Newcastle upon Tyne (three castles) closed in 1884

- Exeter (a Castle) closed in 1883

- York (various marks) closed in 1858

- Norwich (a castle and lion passant) closed in 1702

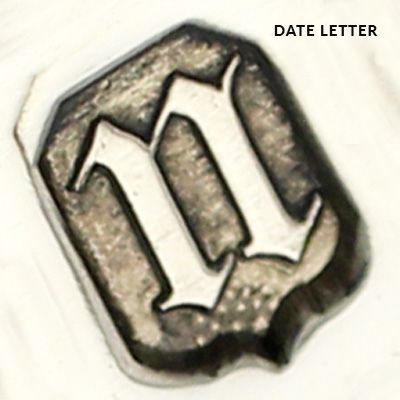

THE DATE LETTER

This hallmark designates the year the piece was assayed. Someone with a keen eye will notice that date hallmarks change from year to year. For example, every date mark consists of a letter and some kind of shape surrounding the letter. Both the letter and its shape combine to designate the year. Each year both change, but not necessarily in a way that makes any sense to those who do not understand silver hallmarks.

THE MAKER'S MARK

As with the date letter, the maker’s mark consists of the maker's initials surrounded by a unique shape. For example, a piece from Henry Charles Freeman would have a rectangular mark with Freeman's three initials within – HCF.

The maker's mark used by Alfred James How also bears his initials, but the shape looks more like a double shield than a rectangle.

THE DUTY MARK

The duty mark indicates that the proper duty was applied to silver pieces when manufactured. A duty mark can be useful for research because it depicts the reigning monarch at the time duty was assessed. The mark was officially discontinued in 1990 with the end of the duty, but it is still important for historical reference on older pieces.

HOW SILVER HALLMARKS ARE APPLIED

Silver hallmarks are said to be struck because of the way they are applied. Markers use a simple hammer and punch that creates a very distinct and sharp image when done properly. However, striking a hallmark can lead to sharp edges and metal spurs, so marking is traditionally done before a piece is polished in preparation for sale. The striking and polishing create a visually stunning image that appears in relief on the piece.

Over the years, a certain amount of patina accumulates in the recessed portions of a mark, giving an already exquisite silver piece even more character. For the buyer or collector who understands the significance of the hallmarks, a well-struck mark that has left a distinct impression makes all the difference in the world. Now you know more about the hallmarks you see on commercially sold silver products.

Thank goodness someone had the foresight hundreds of years ago to start requiring marks in order to verify the quality and authenticity of silver pieces. Today, we revere the hallmarks as a means of both protecting purity and appreciating history.