Scottish Silver Hallmarks

Scotland has been marking silver since the 15th century. In Medieval Scotland, silver was the most important metal used to create highly regarded and powerful items, and provincial silver was given to a lot of churches and places of worship. Quite often, silversmiths couldn’t rely solely on this vocation for their income, therefore most trained in other trades, such as clock making and gunsmithing. One of the earliest references to silver trading was in 1504, when King James IV paid a Dumfries goldsmith to make falconry equipment. In these times, it was also common practice for the customer to bring their own silver to the silversmiths to be wrought.

During the 18th century, Scottish silver reflected the prominent fashions in London, and later, Sheffield and Birmingham. However, some styles of silver are seen as typical Scottish designs, such as that of the bullet teapot, the quaich, and the harsh spoon.

Traditional Scottish Silver

The Quaich is an item known as Scotland’s ‘Loving cup’ or ‘Cup of Friendship’. The word Quaich comes from the Gaelic word ‘cuach’, meaning cup. A traditional element of Scottish silver, the quaich is a shallow cup, with two handles on opposite sides which were carved out of wood or imitation scallop shell. Larger quaiches were also produced for the purpose of drinking ale. The quaich originated in the Highlands, and was first produced in the 17th century. They were originally crafted from wood but later were made out of silver, brass and pewter. The varying materials adhered to the fashions of the upper classes of northern Scotland. The centre of the bowls could often be engraved with ‘SGUAB AS I’ which means ‘Toss it back’ and, as the name suggests, the quaich was used to offer a welcome drink at gatherings whether that be clans, weddings, christenings or to welcome friends into the home.

The Bullet Teapot was another popular item often crafted in Scottish sterling silver. Bullet teapots have a spherical form, and are mounted on a footing. They were popular during the Georgian period, with some of the finest examples being made by William Ayton and Edward Lothian.

The Harsh Spoon is a serving spoon, normally 30-40 cm long, used to serve meat and potatoes.

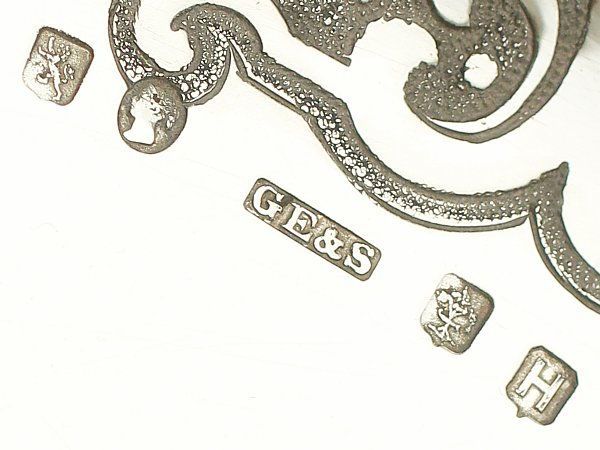

Types of Hallmarks and Town Marks

Thistle Mark

This mark was used from 1759 until 1974 to mark sterling silver (92.5% fine silver and 7.5% other metals). This was Scotland’s national emblem; the lion rampant replaced this mark from 1975 as the standard mark. As legend has it soldiers could hear invaders approaching as they would be wounded by the thistles on the shore.

Lion Rampant

This mark was used in Glasgow from 1819 until the assay office closed in 1964.This mark is said to symbolize the strength of the Scottish people.

Glasgow Town Mark

The town didn’t have a coat of arms until 1866, a number of symbols and emblems were used before this. These symbols of an oak, bird fish and square all came together to make the town mark and the coat of arms. Again each of the symbols holds its own story, incorporating death to live, a love triangle and a pilgrimage.

The Glasgow office opened in 1819 and was that of one silversmithing company Robert Gray & Son. The town mark is a tree, a fish and a bell. The assay office closed its doors in 1964.

Edinburgh Town Mark

This mark is the three towered castle, this was taken from the coat of arms and used from 1485 to the present day. Castle Rock has been protecting the area since that of c.600 BC. The Edinburgh office is still open today and the only assay office left in Scotland, in fact it’s one of four left in the UK. The history of hallmarking at the Edinburgh Assay office can be traced back to 1457. This was when the Incorporation of Goldsmiths of the City of Edinburgh was established.

Antique and Vintage Scottish Silver for Sale

plore our fine collection of antique and vintage Scottish silver for sale. Our collection includes Scottish silverware from the Victorian and Georgian periods and often crafted by collectable silversmiths of the period.

Scotland’s Assay Office’s and Hallmarks

Edinburgh

The only Scottish assay office that remains open today is in Edinburgh (one of the mere four left in the UK). First opened in 1457, this office was where the Incorporation of Goldsmiths of the City of Edinburgh was first established. When hallmarking was first initiated here, it could only be carried out directly by the Deacon (otherwise known as ‘head of the craft’). The town mark of Edinburgh is a three towered castle, an example of which can be seen clearly on this Scottish silver tazza we have here at AC Silver. This mark was accompanied by the maker’s mark and the deacon’s mark until 1681. After this, an assay master was appointed to oversee the process (the first of whom was John Borthwick), and a ‘date letter’ system was introduced. Hallmarks prior to 1759 have an additional Assays Masters Mark, which was replaced by the thistle mark in 1759. The thistle hallmark was used from this point up until 1975, when it was replaced with the rampant lion mark. The Assay office that is open today was transformed from a former church built in 1816, and was reopened by Princess Anne in 1999.

Glasgow

For some time, there was also an Assay office in Glasgow. It was open from 1819 to 1964 and was originally affiliated with the silversmith company ‘Robert Gray & Son’. The town mark for Glasgow is a tree, a fish and a bell, although items produced during the 17th century were marked similarly to the way in which other Scottish provincial towns were.

Scottish Provincial Silver

Despite Edinburgh and Glasgow housing the main assay offices, it was not often that silversmiths actually sent their items to either of these cities to be hallmarked. Consequently, many items were only marked with the maker’s initials and with the town the item was crafted in. This was generally in order to avoid the duty charge which was re-imposed in 1784. These provincial marks grew less common after 1860, rendering provincial Scottish silver quite collectable.

There was a much wider area of manufacture in Scotland than in England, and therefore many hallmarks for smaller areas. Some provincial hallmarks include:

- Perth: Lamb and flag, the sign of St. John

- Aberdeen: ADD

- Elgin: ELN

- Banff: BA

- Inverness: INS, or a mark of a camel

Scottish Silversmiths

Coline Allan Circa 1740-1774 of Aberdeen

Celebrated for the fact that he had mastered multiple trades, Coline Allan was both a silversmith and a watch maker. In addition to these crafts, he also founded a factory for making granite slabs, table tops and chimneys.

William Ayton Edinburgh (1739-40)

This silversmith made many items, varying from salvers to bullet teapots and tea urns. A candleholder and pair of candle snuffers from William Ayton can be found in the national museums of Scotland.

Hamilton & Inches (1866 – present)

This company was founded by Robert Kirk Inches and his uncles James Hamilton in 1866. For the first two years, one would take a night shift while the other slept in order to protect their wares from thieves. During the next twenty years, the company’s reputation increased rapidly, and in 1887, Robert Inches was granted the revered title ‘His Majesty’s Clockmaker’ (a title which is said to date from the reign of James I and IV). Hamilton & Inches is the only Scottish manufacturing goldsmiths company to survive from the 19th century, and continues to flourishes today.

Coats of Arms for Cities of Scotland

Aberdeen

Three castles encased in a red and gold emblem with a lion on each side on their hind legs holding the emblem. These castles are said to represent the defensive during the reign of King Robert.

Arbroath

The mark of the portcullis. Said to symbolize strength and stop the upraise of its people.

Conongate

–A stags head. Said to be representing an attack that be ford King David I against a stag.Dundee

Three lilies in a double handled vase which first appeared in 1416. It is said to symbolize St Mary and the flowers are to show purity and strength.

St Andrews

A diagonal cross. This symbol has a few stories behind it; one dating back to Greek methodology the other about the legend of king Ungus fighting the English in the late eighteen century. Never the less this is the national flag of Scotland.

Elgin

The mark depicts St Giles of France who became the patron of Elgin (said to be because of ancient ties between Scotland and France). The mark is the saint protecting himself from behind an arrow. This is said to again come from when the saint was wounded by a huntsman.

Forres

The mark of Nelson’s tower which is at the top of Clunny Hill. The tower was built as a memorial to Admiral Nelson in 1808 in victory over Napoleons fleet in 1805.

Greenock

This was established as a port in 1669 and the mark for the area became an anchor which was to show the importance of shipbuilding in the area.

Inverness

The camel of the town represents the eastern trade links for the burgh and was used as early as 1760. Later the coat of arms was changed to a camel and an elephant; however the burgh lost its coat of arms in 1975.As mentioned earlier these marks all have a story from where they were punched and tell us why the hallmarks were made for that area. Silversmiths used to travel around a lot which is why you may see the initials of silversmiths with different town marks. Up until 1964 there were two assay offices in Scotland, one in Edinburgh and one in Glasgow to which only Edinburgh now remains. It was seldom that silversmiths sent their items of silver to be hallmarked at the Edinburgh or Glasgow offices. Items were only marked with the maker’s initial and with the town the item was crafted in. This was usually done to avoid the duty charge which was re-imposed in 1784. That’s why for up to the period of 1860 there is more town marked plate than there is duty marked silver. Items produced in the 17th century were marked similar to that of other Scottish provincial towns.