The Rococo Style

Otherwise referred to as ‘late baroque’ or a derivation of ‘rocaille’, the Rococo style characterised European art and design for the first half of the 18th Century. The most prominent design feature of the Rococo era was a desire for over-exuberance ornamentation. There was nothing reserved and restrained about this style and it focused on illusion and theatricality. Other classic features of the Rococo style include flowing, curving shapes; the use of whites and pastel colours with gilding - creating a soft and whimsical aesthetic but with striking features. Bow motifs, flowing shapes and asymmetrical floral design are classic examples and can be seen in this Rococo Murano glass chandelier, and interior feature of Ca'Rezzonico in Venice.

We can trace the origins of the style back to France; the Rococo definition usually encompasses the popular style throughout the reign of Louis XV. The fluid exuberance of the Rococo era is commonly considered to have been a reaction to the previous controlled and rigid style which dominated during Louis XIV’s reign.

Compared to other, larger art movements, Rococo was relatively short lived. From its origin in the 1710s, it went on to peak in popularity during the 1730s, and then saw its demise in the 1750s at which point it was eclipsed by the ride of the Neo-classical style. Although it is sometimes considered as ‘late baroque’ there were key differences, the main of which being the change in mood. Where Baroque took itself more seriously, with its focus on symmetry and bold regal colours, Rococo was far more frivolous. The colours used during the Rococo era were lighter and softer, creating a more playful sensibility.

Rococo also focused almost entirely on interiors, whereas Baroque was highly concerned with the exterior architecture of buildings. Although both Baroque and Rococo feature heavy ornamentation and take inspiration from nature, Rococo certainly pushes these ideas to the extreme.

The word "Rococo” itself is derived from the French "rocaille”, which translates as "rock work”. Rocaille was a method of ornamentation used commonly during the renaissance, which used pebbles, seashells and cement applied on surfaces such as mirrors or porcelain to decorate grotto's and fountains. One of the influences we can see transferred from rocaille to Rococo is the ‘development of the line’: this meant that lines were elongated, twisted and curved to form elaborate patterns, a trend that prevailed in Rococo design. The term ‘rocaille’ was first used in print to refer to a particular Rococo design type in 1736 by the designer and jeweller Jean Mondon ("Premier Livre de forme rocquaille et cartel”).

After being pioneered by French design, Rococo saw its popularity spread throughout Europe throughout the early 1700s. Bavaria, Austria, Germany and Russia all embraced the frivolous style along with its playful and witty themes. Of course, the Rococo style did not stop at interiors; it had its effect upon fashion, art, music, jewellery and silver design.

Zairon [CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons

Ca' Rezzonico [CC BY-SA 4.0], via Wikimedia Commons

Rococo Jewellery

Akin to the rest of Rococo design, jewellery featured flowing lines and seemingly endless movement. The concept of symmetry which had reigned strong throughout the Baroque age was now disregarded and replaced by playful abstract shapes. This move towards the asymmetrical meant leaving behind neatly organised sets of gemstones and pieces of jewellery that relied on a symmetrical aesthetic- such as three pearl pendants. Instead, Rococo introduced complex patterns into its jewellery design featuring ribbons, feathers and foliage.

Some Rococo jewellery designs were elaborate and eccentric. Necklaces became an important statement piece (due to the fashion of a low-cut dress or "décolleté”), allowing large jewels to be displayed proudly. Necklaces often featured multiple festoons, which would highlight a central pendant and may incorporate a typical Rococo motif such as a cross or a bow.

A simple pearl necklace retained its popularity stoically. In fact, in comparison to other elements of design, Rococo jewellery remained relatively reserved, influenced by changes in fashion; the emphasis on flowing lines lead to flowing layers of fabric and a move away from the tight constricting dress sense (such as corsets) of the previous years.

The move towards exuberant clothing and interiors may have meant that jewellery had to be slightly played down, as to compliment all the other busy ornamentation. Simple strings of pearls or diamonds were favoured, as was the even simpler option of a ribbon tied around the neck. Other popular types of jewellery included girandole earrings and items featuring arabesque motifs.

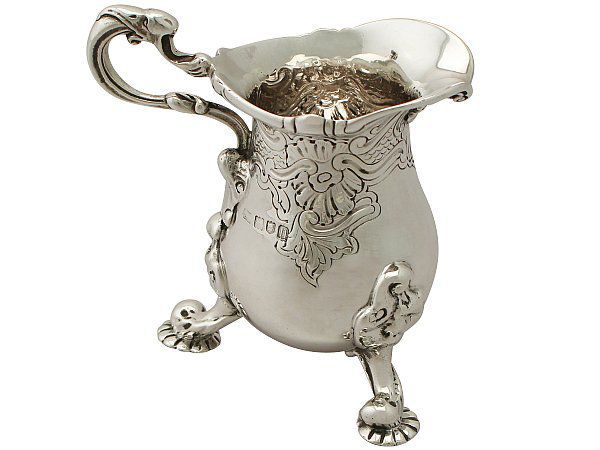

Rococo Silver

Similarly, to the designs seen in jewellery, silver design celebrated asymmetric ornamentation. Silverware from this period also featured natural motifs including rocks, shells, plants and marine items. A particular emphasis was put on the shells and flowing wave-like lines. Ornamentation was in no way reserved, with the elaborate style of Rococo interiors reflected strongly in silver design. The Rococo period did not see much innovation in terms of form as it was the ornamentation that was developed in silver design.

Key Rococo Silversmiths

Juste-Aurele Meissonnier (1695-1750): A silversmith from Turin, Meissonnier was a member of the goldsmith’s guild in Paris from 1725. He embraced the flamboyance of the Rococo style crafting items which featured flowing lines, giving the illusion of constant movement. His only surviving item is a gold snuff box which was crafted in 1728.

Thomas Germain and his son Francois: Parisian designers, and at the heart of the cultural movement, these silversmiths were both highly acclaimed. They were both commissioned by the King of Portugal which, luckily for us, meant that a large amount of their work was overseas and therefore survived the French revolution (1789-99); not all silverware from this time was so fortunate. Much of their work can now be seen at the Museo Nacional de Arte Antiga, Lisbon. Unfortunately, and despite his father’s help and reputation, Francois fell bankrupt in 1765 and consequently forfeited his royal appointments.

Paul de Lamerie (1688- 1751): Perhaps the most well-known Rococo silversmith today, this period cannot be discussed without recalling his work. Born in the Netherlands in 1688, Paul de Lamerie pioneered the combination of elaborate French design/ornamentation with the highest quality British silver. This combination and his expertise has rendered him one of the most well-known and collectable silversmiths in British history. Here at AC Silver we are privileged enough to have some rare and exquisite items by Paul de Lamerie in our inventory.